When cognac was invented in the seventeenth century, it was sold in casks. The practice of bottling cognac only started halfway the nineteenth century. And very soon afterwards the first labels appeared. This was a very imported way to distinguish one brand from another and to gain brand awareness.

The oldest known labels were made by Martell and they date back to 1849. It is a little curious that this did not happen earlier on, because the first labeled winebottles had already appeared more than 50 years earlier, at the end of the eighteenth century.

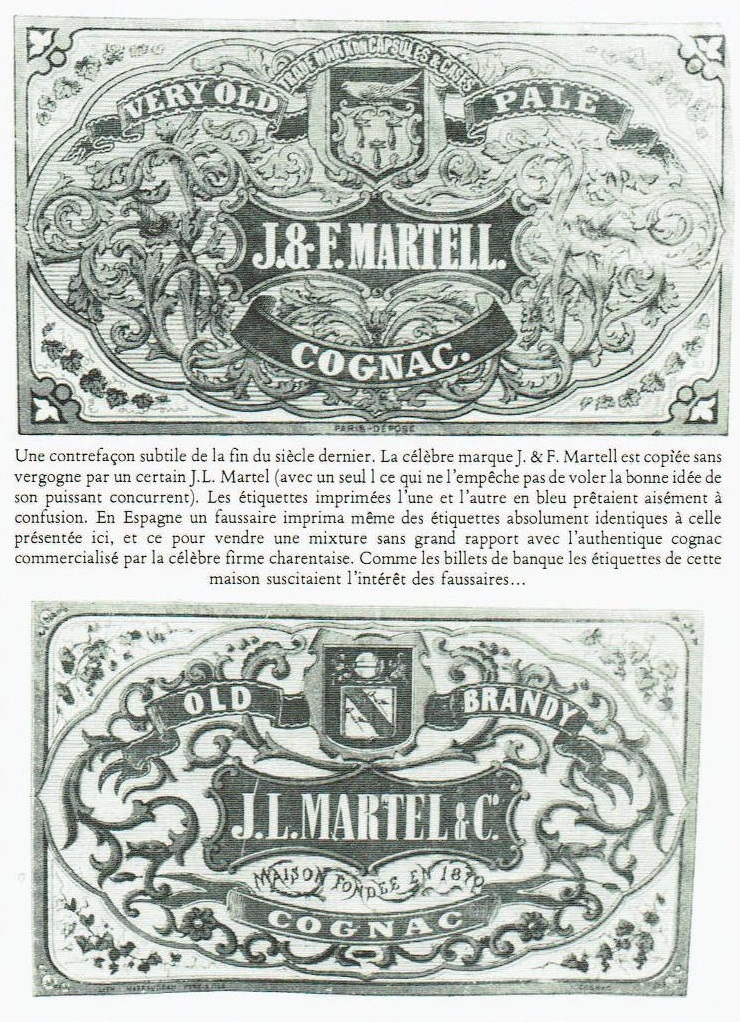

These first labels of Martell had a blue colour and a rectangular shape and it is a label they hang on to for a very long time. Depicted were stylisticly designed vine branches and an emblem with the quality mark ‘Very Old Pale’ and underneath the name J. & F. Martell. The emblem portrayed a shield with three mallets (martel means hammer or mallet) and a sitting bird (swallow) on top.

These first labels of Martell had a blue colour and a rectangular shape and it is a label they hang on to for a very long time. Depicted were stylisticly designed vine branches and an emblem with the quality mark ‘Very Old Pale’ and underneath the name J. & F. Martell. The emblem portrayed a shield with three mallets (martel means hammer or mallet) and a sitting bird (swallow) on top.

It did not take long for Hennessy to follow. They of course used their logo of an armed arm, but also stylisticly designed vine branches, this time with some grape bunches. They had a white label with gold coloured printing.

These labels were very successful and many other companies quickly folowed suit, using the designs of Martell and Hennessy as an example. In some cases they were even perfect replica’s and there certainly was talk of misdirection and even forgery (see picture on the left; from Bruno Sepulchre: Le Livre du Cognac). For Jean Louis Martel (with one ‘l’) it was too tempting. His etiquettes were practically the same as the above depicted Martell label. He of course had to change them.

On the 23d of June 1857 a new law comes into force provisioning the deposition of a brand name and a distinguishing mark. This law was not only in force for cognac. The first deposited brand name of cognac was O. Planat in 1859.

Hennessy and Hine followed in 1864, Hennessy of course with his arm, armed with an axe and Hine with his deer.

A frequently used method was chromolithography. For this reason the use of colours was usually restricted to one or two colours.

A frequently used method was chromolithography. For this reason the use of colours was usually restricted to one or two colours.

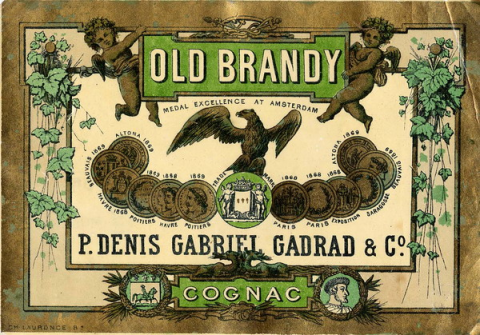

The upright oval label was fairly often used in the second half of the nineteenth century. The use of grapes and grape leaves in the picture was also very common. Sometimes even the shape of a grape leaf was used as the shape for the whole label. Figures of little angels were also very widely used.

Another custom that was soon adopted by many producers was the mentioning of prices they had won on exhibitions. Invariably this was done in the form of a medal and some labels had a lot of medals depicted, sometimes up to ten. During this time the rectangular shape gradually pushed to the fore.

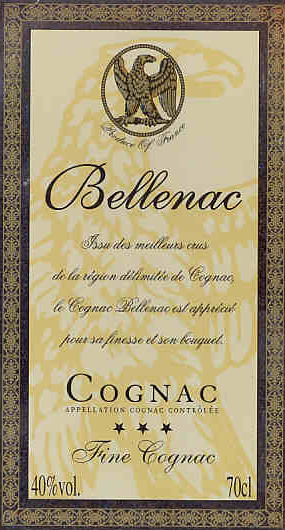

At first only the name of the producer was on the label, together with the statement that there was cognac inside. From 1865 on we  see the practice coming into existence to use stars on the label as a manner to state the age of the cognac, Hennessy being the first to start this. He uses one star for his two year old cognacs, two stars for four years old cognacs and three stars voor cognacs that have aged for six years.

see the practice coming into existence to use stars on the label as a manner to state the age of the cognac, Hennessy being the first to start this. He uses one star for his two year old cognacs, two stars for four years old cognacs and three stars voor cognacs that have aged for six years.

For quite some time this custom was not adopted by others, but other statements were used on the labels, like ‘pale cognac’, ‘cognac rassie’ (matured), ‘vieille cognac’ and others.

A few years later, in 1870, Hennessy starts using the indication XO for his oldest and best cognac. Hennessy did not deposit this indication as his property XO, nor did he register the use of stars. In the years to follow many producers adopt these symbols on their labels.

Other symbols are also used, like crowns that were initially used by Hine in stead of stars.

Even before the turn of the century the custom to use symbols as an indication of age is growing: V.O.P., S.O.P., V.S.O.P., V.V.S.O.P. and so on. But even so, this was by no means a guarantee. Only after World War Two the ‘compte’-system was introduced, that included governmental control on the ageing of cognac.

Even before the turn of the century the custom to use symbols as an indication of age is growing: V.O.P., S.O.P., V.S.O.P., V.V.S.O.P. and so on. But even so, this was by no means a guarantee. Only after World War Two the ‘compte’-system was introduced, that included governmental control on the ageing of cognac.

The indications we know today (VS, VSOP and XO) were only introduced much later by the Bureau National Interprofessionel de Cognac (the B.N.I.C.), and they were defined with great clarity: the youngest eau-de-vie in a bottle VS, VSOP or XO must have a aged in a cask for a minimum of 2, 4 and 6 years respectively, taking the 1st of April following distillation as a starting date. jaar op fust hebben gelegen, gerekend vanaf 1 april volgend op de destillatie. For more on the topic of age and ‘comptes’: see ‘comptes’ on the page on age.

In the eighteennineties the pictures became more frivolous and even eccentric sometimes, like Robinet using an elephant, Jules Villac with a camel, Albert Darmon with a sailor, Prunier using a canon that firs a bottle, Mathusalem portraying a nude grey0haired man with a scythe, holding a glass of cognac, etc. For the foreign market for certain the labels could be quite extravagant.

Just take a look on Paul Ronne’s website; under the heading ‘Insolites’ he has some very special and peculiar old labels.

The pictures were of course influenced by contemporary trends and art forms. When at the end of the nineteenth century Art Nouveau appeared, it was evident in the labels also: beautiful round and curving lines and pictures that were in harmony with nature.

Actual historical events can also influence the pictures on labels. Several examples of mentioning the First World War are to be seen. And historical figures are also widely used: Louis XIV and of course Napoléon.

After the turn of the century, around Wolrd War One, the labels became much more frugal, emulating the characteristics of a wine-etiquette.

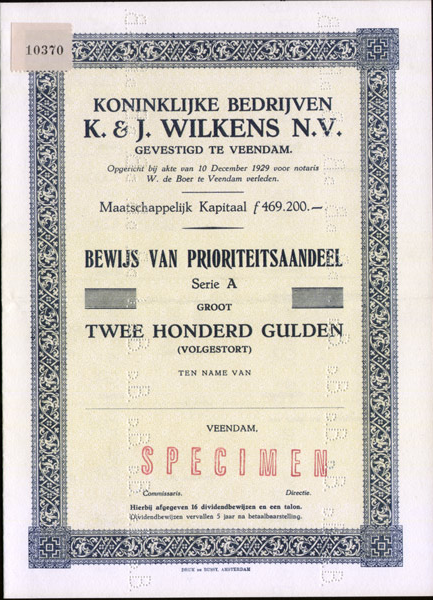

After the First World War they became more tight, printed on watermarked paper, cream-coloured with black or sometimes coloured, decorated, Art-Déco like borders that reminded of an old-fashioned security-paper.

Until this period of time not a lot of information is to be seen on the labels. The brand name, the mentioning of cognac and maybe the statement that it is an old cognac. Also mentioning of prices if a producer had won one. The labels were decorated, sometimes with an exotic picture, often with grapes or wine branches and with embleme’s and logo’s. Only later on other information appears: quality marks, age indications, the name of a village or district of the producer, year of establishment and sometimes the name of the place were the cognac was bottled. Much later a postal code is added.

Today most labels have a rectangular shape, have scanty decoration and usually bear an emblem or logo, but always give the neccessary information: name of the brand, quality indication, age, percentage of alcohol, name of the producer and his address.

Today most labels have a rectangular shape, have scanty decoration and usually bear an emblem or logo, but always give the neccessary information: name of the brand, quality indication, age, percentage of alcohol, name of the producer and his address.

A small number of producers distinguish themselves by using a different form of the label or a modern look. But the public does not seem to be very enthousiastic about it, because these experiments usually tend to disappear very fast.

In the seventees the age indications VS, VSOP and XO were widely used. They still are, but since some time now other more faishonable indications are coming into se like ‘très vieille’, ‘réserve familiale’, ‘ancestral’ and the like. Also ‘Très Rare’ like on this bottle here from Paul Giraud. These appellations are also regulated by the B.N.I.C. (see the page on ages).

A fully new development are bottles without any labels at all! Many of the major firms use crystal decanters for their top-segment cognacs and they engrave the name of the producer together with a logo and product name directly on the glass. Most often these decanters are packaged in cardboard boxes or even wooden boxes and additional information on the contenance and production process is provided separately.